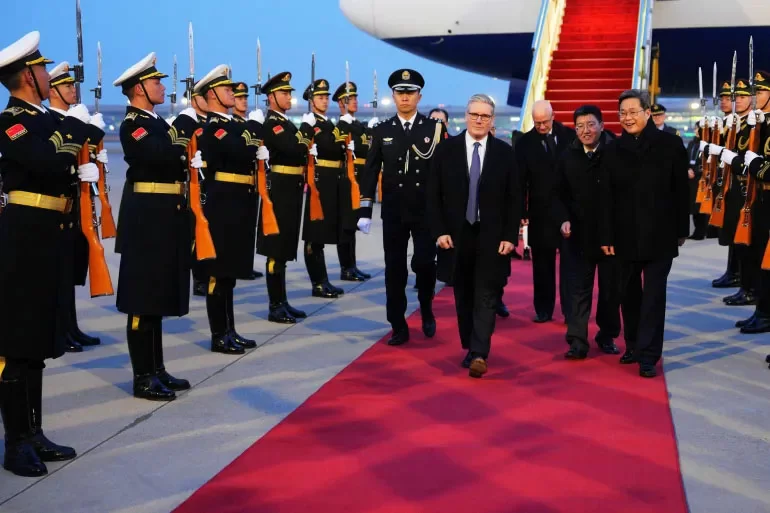

In a significant geopolitical shift, China is strategically positioning itself as a stable trade and diplomatic partner for traditional U.S. allies increasingly alienated by Washington’s unpredictable policies under President Donald Trump. The first month of 2026 has witnessed an extraordinary diplomatic procession to Beijing, with Chinese President Xi Jinping hosting South Korean President Lee Jae Myung, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, Finnish Premier Petteri Orpo, and Irish Taoiseach Micheal Martin. This week, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer commenced a three-day official visit to China, while German Chancellor Friedrich Merz is scheduled for his inaugural China visit in late February.

Five of these visiting nations are formal treaty allies of the United States, yet all have faced retaliatory trade measures from the Trump administration throughout the past year. These included punitive tariffs on critical exports such as steel, aluminum, automobiles, and automotive components. Recent NATO tensions further strained relations after Trump proposed annexing Greenland and threatened additional tariffs against eight European nations, including the UK and Finland, though these threats were subsequently retracted.

China has long advocated for an alternative to the U.S.-led international order established post-World War II. This message gained renewed urgency during the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, where Trump boasted of America as ‘the world’s hottest country’ due to growing investments and tariff revenues, while simultaneously urging Europe to follow Washington’s example. In contrast, Chinese Vice Premier Li Hefeng emphasized Beijing’s commitment to multilateralism and free trade, criticizing ‘unilateral trade measures by certain countries’ that violate fundamental WTO principles and disrupt global economic stability.

According to Bjorn Cappelin of Sweden’s National China Centre, China is successfully cultivating an image as a ‘stable and responsible global player’—a portrayal particularly resonant with Global South nations. John Gong, economist at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing, notes that recent European leadership visits signal that the Global North is also attentively listening. Positive developments include Britain’s approval of a massive Chinese embassy complex in London and progress in resolving trade disputes regarding Chinese electric vehicles entering European markets.

Canada’s renewed engagement was exemplified by Prime Minister Carney’s landmark visit—the first since Justin Trudeau’s 2017 trip—resulting in agreements reducing Chinese tariffs on Canadian agricultural exports and Canadian tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles. This visit also marked a breakthrough in relations that had been frozen since the 2018 arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou and subsequent detention of two Canadian citizens in China.

However, former U.S. diplomat Hanscom Smith cautions that China’s appeal has limitations. ‘If the U.S. becomes more transactional, a vacuum emerges, but it’s uncertain whether China, Russia, or any other power can fill it,’ he observed. Concerns persist regarding China’s massive trade surplus, which reached $1.2 trillion last year—partially amplified by Trump’s trade war that pushed Chinese manufacturers to relocate production to Southeast Asia and develop new non-American markets.

Some European leaders, including President Macron, have expressed apprehension about China’s ‘massive overcapacities and disruptive trade practices’ such as export dumping. Vice Premier Li addressed these concerns in Davos, stating: ‘We never pursue trade surplus; besides being the world’s factory, we hope to become the world’s market. Often China wants to buy, but others don’t want to sell. Trade issues sometimes consequently become security problems.’