A recent confrontation between Surinamese authorities and timber exporters has revealed profound systemic failures in the nation’s regulatory enforcement framework. What initially appeared as an isolated incident involving wood exports to India has instead exposed fundamental weaknesses in rule-of-law implementation.

In late October 2025, Agriculture Minister Mike Noersaliem issued a stern warning to all timber companies, explicitly stating that non-compliant operations would no longer receive mandatory phytosanitary certifications from the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries (LVV). This action came after discoveries that several exporters had been shipping wood without meeting national and international standards.

Six timber enterprises have positioned themselves as victims of what they term ‘sudden government intervention,’ claiming the minister’s directive introduced unexpected new requirements. This argument proves both legally and factually untenable. Phytosanitary certification constitutes a legal obligation derived from national legislation and international treaties, not merely policy preferences of individual ministers. Established exporters have operated under these requirements for years.

The ministry’s communication represented not the introduction of novel regulations but rather enforcement of existing mandates—a crucial distinction. In any rule-of-law society, businesses cannot legitimately appeal to ‘established practice’ when knowingly operating in violation of requirements, whether dealing with timber, fish, rice, gold or any other export commodity.

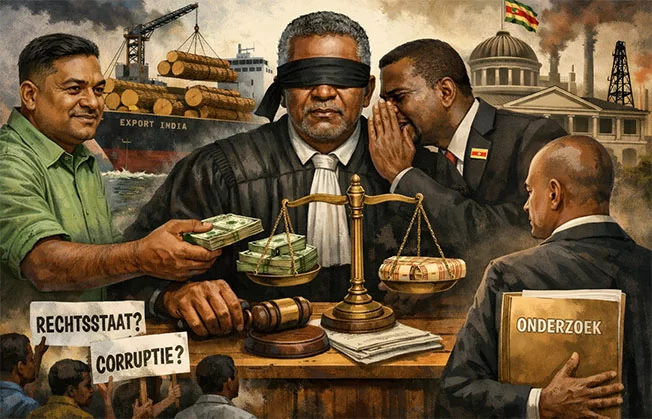

The central inquiry therefore shifts from why Minister Noersaliem enforced regulations to why previous administrations apparently did not. If current timber shipments failed compliance standards while previous exports received certification, only two conclusions emerge: systematic regulatory neglect or active complicity in rule-breaking. Both scenarios indicate serious governance failures where systematic non-compliance creates fertile ground for corruption, conflicts of interest and political manipulation.

Most alarmingly, judicial intervention has compounded these concerns. The cantonal judge avoided addressing the core issue of regulatory compliance, instead prioritizing arguments about irreversible financial damage. This establishes a dangerous legal precedent suggesting that those who act quickly, ignore regulations, and subsequently threaten financial claims can force the state into retroactive authorization.

The implications extend far beyond timber. Rice exporters investing in certification, fisheries undergoing international audits, gold companies struggling with compliance, and vegetable exporters meeting strict European standards now face distorted incentives. Why maintain strict adherence when precedent demonstrates that violation pays?

At the strategic level, Suriname’s credibility faces imminent jeopardy as the nation approaches large-scale oil and gas production. These industries fundamentally depend on certification, compliance and local content requirements. Surinamese businesses must demonstrate adherence to international standards regarding safety, environment, quality and governance—not as paper formalities but as verifiable practices.

How credible appears Suriname’s commitment to compliance if certificates can be coerced under pressure? How convincing becomes our narrative to international partners and investors if regulations prove negotiable for the sufficiently powerful? In petroleum industries, reputation constitutes everything. A single perception of flexible regulations could cost millions in investments and exclude local companies from participation.

This case transcends six timber companies versus the state. It represents societal injustice where economic power hijacks legal principles, where influential entities place themselves above the law and, worse, manipulate legal frameworks to their advantage. Unless the state establishes clear political and judicial boundaries, we risk legitimizing an economy where compliance becomes optional and integrity subordinate to pressure.

Should the National Assembly refrain from launching parliamentary investigations and the Public Prosecutor’s Office neglect examining potential criminal offenses, they effectively confirm that capital outweighs justice in Suriname. Such outcome represents not governance but organized lawlessness.