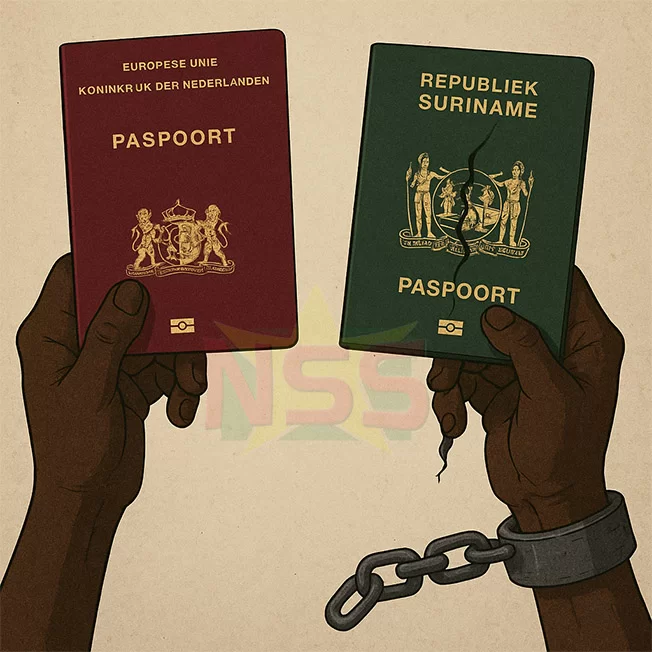

Fifty years after Suriname gained independence from the Netherlands, one contentious issue remains persistently relevant: the Dutch passport. This document has evolved beyond mere travel authorization to become a tangible manifestation of unresolved historical inequalities stemming from the colonial era that continue to shape contemporary societal dynamics.

The practical advantages of possessing a Dutch passport create a stark divide among Surinamese citizens. Those holding the coveted burgundy-colored document enjoy unparalleled mobility, visa-free access to numerous countries, enhanced consular protection, and greater economic opportunities. In contrast, Surinamese passport holders face significant barriers, including arduous visa application processes, intense scrutiny of financial standing, and implicit questioning of their credibility when seeking international travel.

This disparity becomes particularly evident during international transit. At airports like Schiphol, Dutch passport holders can freely exit transit areas, rest in hotels, or explore during layovers. Meanwhile, those without equivalent travel documents may remain confined to transit zones for up to twenty-four hours—a physical manifestation of the inequality embedded in citizenship hierarchies.

The phenomenon extends beyond travel logistics into societal participation. Surinamese-Dutch citizens actively contribute to Suriname’s organizational structures and public discourse, yet retain the security of European Union protection when risks emerge. This dynamic creates an implicit power asymmetry where emotional connection to Suriname doesn’t necessarily translate to shared vulnerability or consequence.

Language and cultural expressions further reveal enduring colonial mentalities. Phrases like “That’s just Indian stories” (dismissing narratives as exaggeration) or “When black man eat, black man sleep” (implying laziness) perpetuate harmful stereotypes rooted in colonial justification narratives. These linguistic patterns continue to devalue indigenous knowledge systems and reinforce hierarchical thinking.

The ongoing debates surrounding passport privileges ultimately transcend practical concerns about mobility, touching upon fundamental questions of dignity, recognition, and equal treatment. The emotional connection to Surinamese identity exists independently from the geopolitical value of one’s citizenship documents, yet the world continues to make consequential distinctions based on passport colors.

Addressing these disparities requires honest acknowledgment of the parallel realities: the emotional landscape of national identity versus the geopolitical realities of passport privilege. Only through this recognition can meaningful dialogue begin toward establishing more equitable connections that honor both historical context and human dignity, regardless of which document one carries.