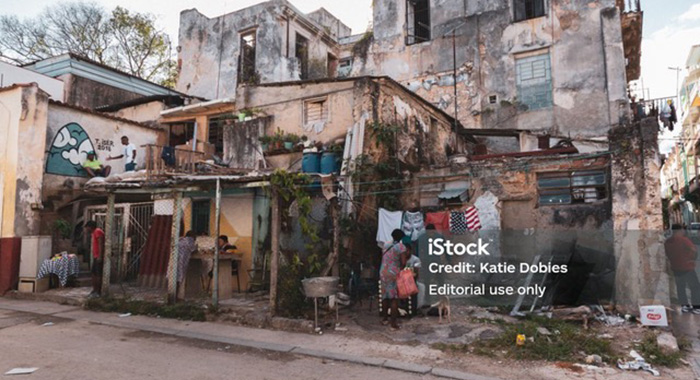

A persistent narrative among many Vincentian commentators—encompassing politicians, community activists, and the general public—attributes Cuba’s enduring economic hardships, including widespread poverty, food insecurity, and substandard housing, primarily to the longstanding United States economic embargo, colloquially termed ‘el bloqueo’ by Cubans.

While this comprehensive framework of economic, commercial, and financial sanctions was initially implemented in the early 1960s, it has not entirely isolated Cuba from global trade. The nation has consistently engaged in international commerce throughout its history. Current economic constraints are more intricately linked to the cessation of aid from its former patron, Russia, decades of detrimental collectivist economic policies, flawed political governance, and a significant ‘brain drain’ of its most skilled and productive citizens—a challenge also familiar to St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

As the most protracted trade embargo in modern history, it continues to attract significant international scrutiny, though its foundational causes are frequently minimized or omitted in contemporary discourse. The embargo’s origins are deeply rooted in the illegal nationalization of American-owned assets by the Cuban government following the 1959 revolution. Under Fidel Castro, the state seized oil refineries, sugar mills, and utilities, predominantly without compensating their U.S. owners. This action remains a pivotal legal impediment; the U.S. Department of State asserts that resolving approximately $7 to $8 billion in certified claims for confiscated property is a prerequisite for any full lifting of the sanctions.

The Cold War geopolitical landscape provided a second critical justification. The U.S. aimed to isolate the Castro regime to curtail the proliferation of Soviet influence and communist ideology in the Western Hemisphere. This strategic concern was dramatically amplified in 1962 during the Cuban Missile Crisis, triggered by the discovery of Soviet nuclear missiles stationed merely 90 miles from Florida. This event prompted President John F. Kennedy to escalate a partial trade ban into a full embargo, a measure deemed essential for hemispheric security.

In subsequent decades, the embargo’s rationale evolved to emphasize catalyzing political reform to liberate the Cuban populace from communist rule. Landmark legislation, including the Cuban Democracy Act (1992) and the Helms-Burton Act (1996), codified the sanctions into U.S. law. These acts stipulate that the embargo can only be rescinded upon Cuba meeting specific democratic conditions, such as legalizing political opposition, conducting free and fair elections, releasing political prisoners, and guaranteeing freedoms of the press and association.

Further complicating the relationship, the United States has designated Cuba as a state sponsor of terrorism on multiple occasions (1982–2015 and again from 2021 to present). More recent U.S. concerns, which critics now emphasize, center on Cuba’s sustained support for the Nicolás Maduro regime in Venezuela—a government accused of electoral fraud, harboring U.S. fugitives, and maintaining alliances with U.S. adversaries like Russia, China, and Iran.

Domestic U.S. politics, particularly within the influential Cuban-American community in Florida, also play a substantial role in perpetuating the policy. This constituency, often holding a hardline stance against the Cuban government, represents a sensitive political consideration for both major American political parties. Projecting into early 2026 under a hypothetical second Trump administration, the policy has intensified into a ‘total pressure’ campaign, featuring an oil blockade designed to further cripple the island’s tourism and energy sectors. The ultimate question remains whether such escalating pressure will inspire the Cuban people to reclaim their nation from its Marxist leadership.