Jamaica is currently celebrating a record-low unemployment rate of 3.3 per cent, a figure that appears to signal economic progress. However, economists caution that this statistic conceals significant underlying issues, including widespread underemployment, a vast informal sector, and a disengaged youth population, all of which pose threats to the nation’s sustainable growth.

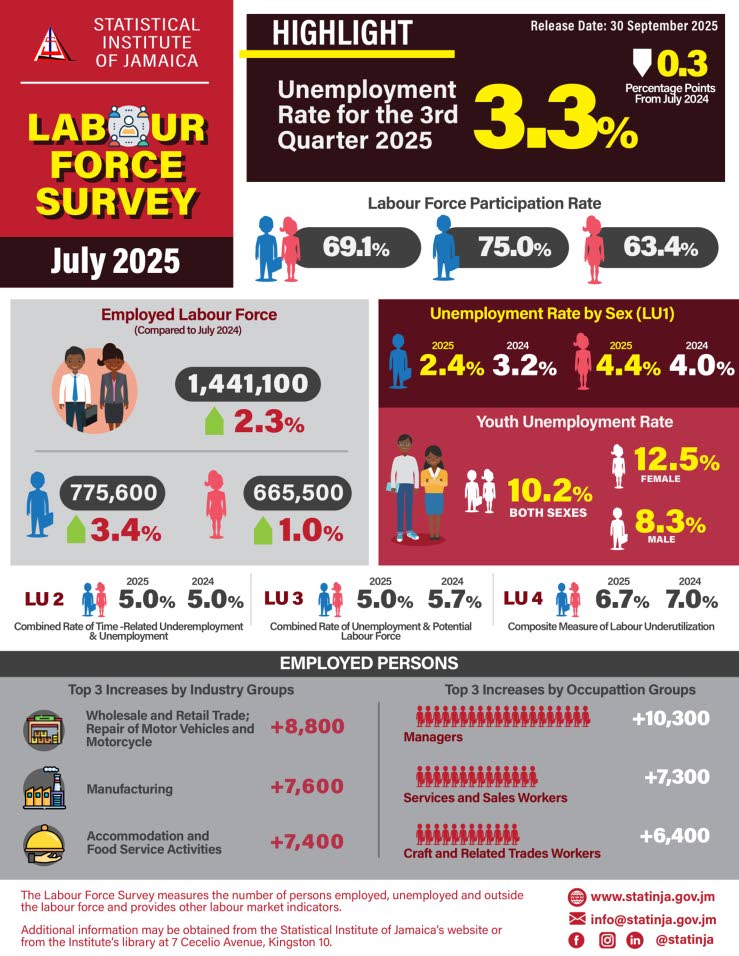

While only 49,200 Jamaicans are officially unemployed, a broader measure of labour underutilisation reveals a more concerning 6.7 per cent rate. Economist Wendel Ivey highlights that just 45 per cent of the 1.4-million-strong workforce is formally registered, indicating that over half of the labour force operates in the informal economy without social protections or job security.

For individuals like D’Angelo, a skilled chef with seven years of experience, this reality is deeply personal. He describes his work as sporadic, relying on event bookings for income. “If an event is happening, we get three or four days for that week, and in other weeks when there is no work, we try to hustle otherwise,” he explains. D’Angelo is one of 25,400 Jamaicans classified as ‘time-related underemployed’—working part-time but desiring and available for more hours. This underemployment, Ivey argues, reflects a misalignment between skills and job opportunities, limiting productivity and earnings potential.

The informal sector exacerbates these challenges. With only 641,495 PAYE taxpayers out of 1.4 million employed workers, Ivey notes that the majority of the workforce lacks formal registration, reducing tax revenues and constraining productivity growth.

A more profound crisis lies in the 124,700 young people classified as NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training), a rate of 25 per cent—well above the Latin America and Caribbean average of 18.3 per cent. Ivey warns that this represents a significant underutilisation of human capital, with long-term implications for the economy.

Job creation trends further complicate the situation. The largest employment increases have been in sectors like wholesale and retail trade, which Ivey criticises for offering limited productivity gains and low wages. This, he argues, reinforces cycles of underemployment and informality, while also contributing to brain drain as skilled workers seek opportunities abroad.

To address these issues, Ivey calls for economic diversification, particularly into manufacturing and logistics, alongside targeted skills development and entrepreneurship programmes for disengaged youth. Until these structural flaws are addressed, Jamaica’s celebrated unemployment rate will remain a superficial victory, masking deeper vulnerabilities in the labour market.